Hermann Stenner

Recto: Ziegelei – Verso: Stehende Madonna

Description

- 1913 was a particularly productive year in Stenner's very short life

- Having died at the age of 23, his mastery is already evident here

- The painting combines working-class culture and popular religion in an expressionist manner

When Hermann Stenner died in the war in 1914, he was 23 years old. He had only been studying painting at various academies since 1908 and his teachers included masters such as Adolf Hölzel, with whom he studied from 1911 and was even allowed to use a master student studio. However, Kandinsky's work also had a decisive influence on the student and young artist. Through academies in Bielefeld, Munich, Dachau and Stuttgart as well as excursions, Stenner became acquainted with a range of artistic styles, experimented - and thus formed his own artistic voice. This is clearly influenced by Expressionism, and there are also borrowings from the southern German painting of the time as well as references to his East Westphalian origins.

In 1914, Stenner volunteered for front-line service and died at the end of the same year. The enthusiasm for the war, which he shared with many other young men of his generation - and also with many artists of his time - ended for Hermann Stenner in the early morning, somewhere before Iłów.

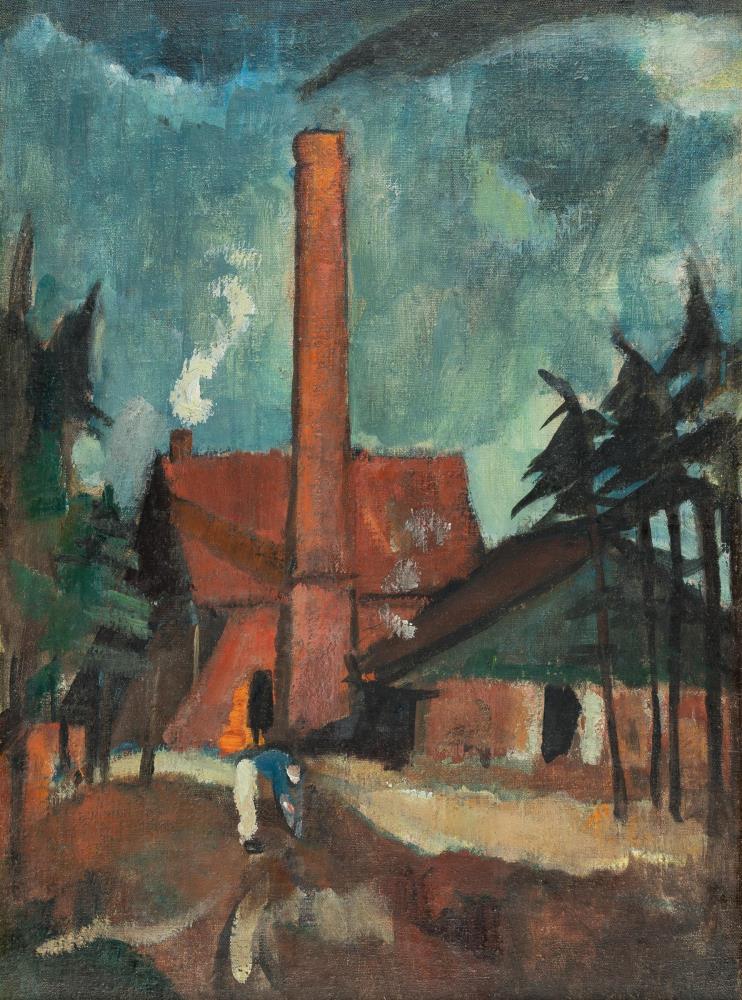

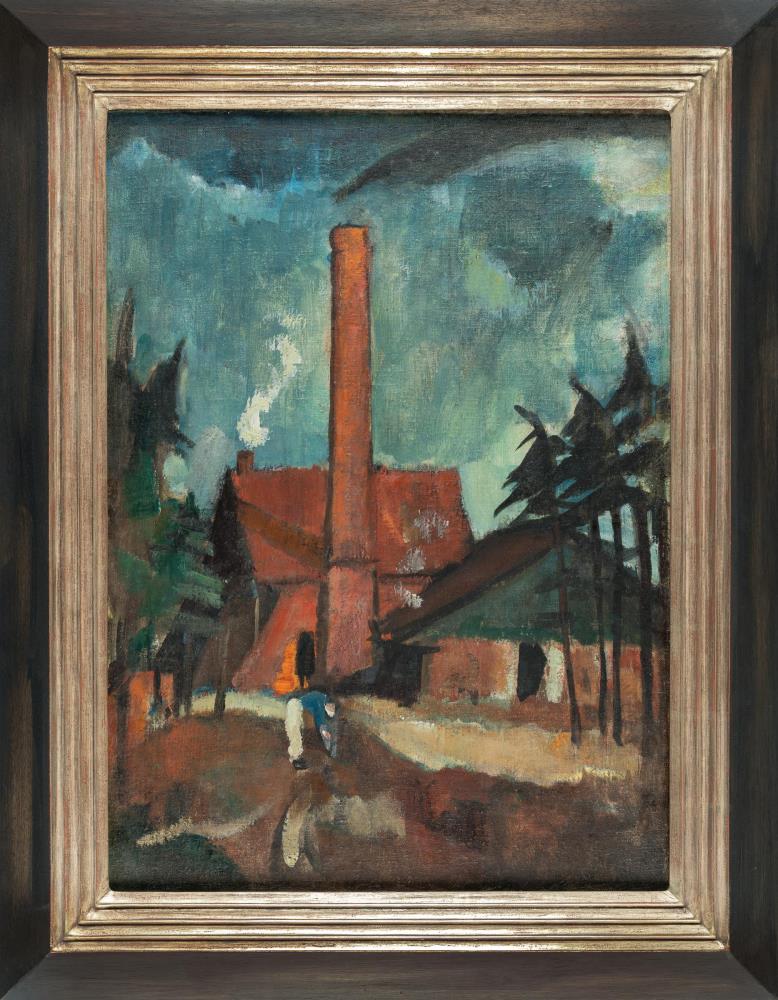

In 1913, Stenner painted the picture offered here. The front - or rather: the side that is thought to be the front - gives us an insight into the world of the workers. The motif of the brickworks appears repeatedly in Stenner's work; another version was removed from the Kunsthalle Bielefeld as "degenerate art" as part of the National Socialist "purges". In our version, the factory's chimneys are smoking and bricks are being fired. The collection of buildings surrounded by tall fir trees seems almost idyllic; a figure in a blue and white robe approaches. Stenner is certainly idealizing, and yet he shows a motif that could not have been more commonplace for many people: The view before the start of the work shift, in the numerous factories of the empire at the beginning of the 20th century.

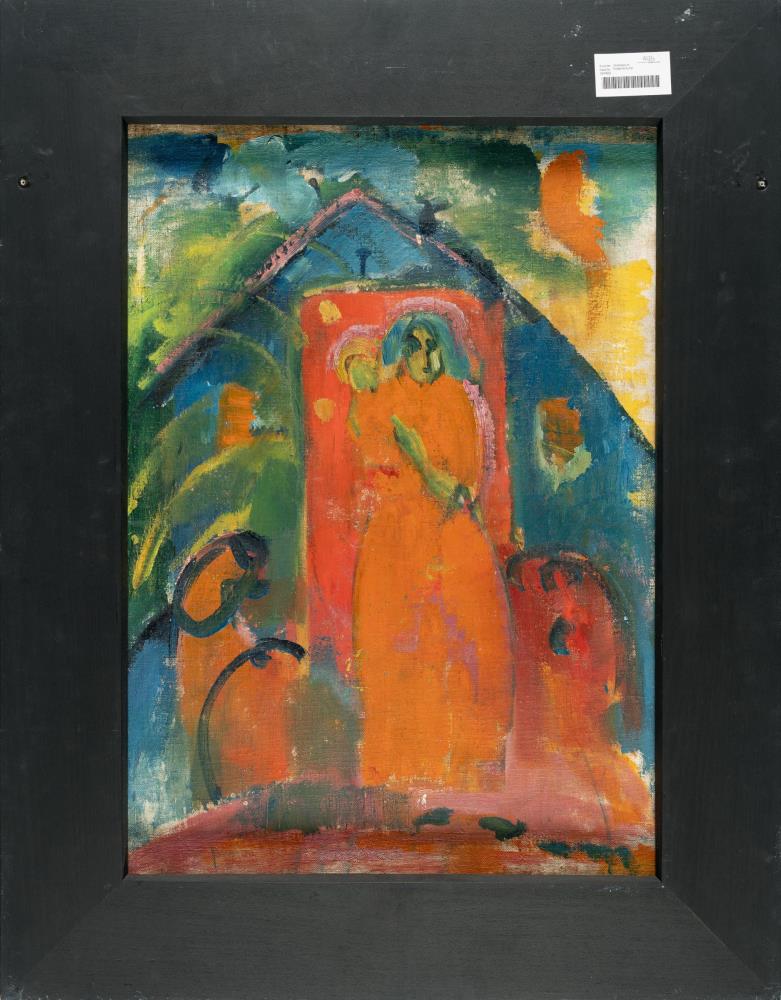

The reverse of the work also shows us what is actually an everyday scene, but takes us into a completely different area of life - or perhaps not? Here we see a Madonna figure, thrown onto the canvas with a quick brushstroke, more a memory sketch than a mimetic reproduction of a discovered scene. Despite its coarseness, the painting radiates an appealing liveliness and intensity through its intense coloration.

Factory and Madonna figure. Everyday work and religion. Sweat and contemplation. What may initially seem like opposites are certainly part of the same work for a reason. Not only are the two aspects two sides of the same coin, but they are both important parts of the lives of the workers, the "ordinary people" whose lives Stenner portrays here.

Hülsewig-Johnen/Reipschläger 141/158.

- Having died at the age of 23, his mastery is already evident here

- The painting combines working-class culture and popular religion in an expressionist manner

When Hermann Stenner died in the war in 1914, he was 23 years old. He had only been studying painting at various academies since 1908 and his teachers included masters such as Adolf Hölzel, with whom he studied from 1911 and was even allowed to use a master student studio. However, Kandinsky's work also had a decisive influence on the student and young artist. Through academies in Bielefeld, Munich, Dachau and Stuttgart as well as excursions, Stenner became acquainted with a range of artistic styles, experimented - and thus formed his own artistic voice. This is clearly influenced by Expressionism, and there are also borrowings from the southern German painting of the time as well as references to his East Westphalian origins.

In 1914, Stenner volunteered for front-line service and died at the end of the same year. The enthusiasm for the war, which he shared with many other young men of his generation - and also with many artists of his time - ended for Hermann Stenner in the early morning, somewhere before Iłów.

In 1913, Stenner painted the picture offered here. The front - or rather: the side that is thought to be the front - gives us an insight into the world of the workers. The motif of the brickworks appears repeatedly in Stenner's work; another version was removed from the Kunsthalle Bielefeld as "degenerate art" as part of the National Socialist "purges". In our version, the factory's chimneys are smoking and bricks are being fired. The collection of buildings surrounded by tall fir trees seems almost idyllic; a figure in a blue and white robe approaches. Stenner is certainly idealizing, and yet he shows a motif that could not have been more commonplace for many people: The view before the start of the work shift, in the numerous factories of the empire at the beginning of the 20th century.

The reverse of the work also shows us what is actually an everyday scene, but takes us into a completely different area of life - or perhaps not? Here we see a Madonna figure, thrown onto the canvas with a quick brushstroke, more a memory sketch than a mimetic reproduction of a discovered scene. Despite its coarseness, the painting radiates an appealing liveliness and intensity through its intense coloration.

Factory and Madonna figure. Everyday work and religion. Sweat and contemplation. What may initially seem like opposites are certainly part of the same work for a reason. Not only are the two aspects two sides of the same coin, but they are both important parts of the lives of the workers, the "ordinary people" whose lives Stenner portrays here.

Hülsewig-Johnen/Reipschläger 141/158.